In late 2021, I circulated a questionnaire to several of my athletes who had been working with me for the majority of the year. The purpose of that was to solicit feedback for goal setting and to plan training for the new year but I also included a request for suggestions for ways that I could be a better coach for my athletes. One responded with a request that I share my experiences in the sport; what has worked for me, what hasn’t, etc.. In this way I could impart some of the lessons that I have learned in my more than two decades of multisport and hopefully help my athletes take the shortcut of not having to learn the same way I did!

I thought that this was an excellent suggestion and so I am going to try and write something up on a regular basis to help you all in this way. As best I can, I will provide something monthly. If you have a specific question or idea for something that you would like me to cover, send it to me and I’ll add it to the list.

For this first installment, I want to cover a topic that took me a long time to really come to terms with and that is the idea that you really shouldn’t get too caught up in trying to buy your way to speed in multisport.

Like many, when I first began in triathlon, I was shocked and amazed to see how high the entry costs were. After you finish shelling out for a bike and a wetsuit you were in a pretty deep hole. Then, when you show up for your first event you take one look around and it is very easy to be seduced by all of the wonderful, speedy looking equipment that everyone else has and before you know it you become convinced that you will never be able to get any better unless you change your gear and that you MUST have something new and shiny to be able to compete with all the cool kids.

Multisport quickly becomes a ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ endeavor and if you aren’t careful you can end up many, many thousands of dollars poorer only to find that now you have cool looking stuff but you are still going exactly the same speed.

I went through this cycle many times. When I started in triathlon I got in to it on a modest budget and at my first couple of races marveled over what was available if only you had the money and the knowledge. I started to read triathlon publications and the more I learned the more I lusted over all the fancy tech that I really could not afford but was convinced was the thing that I needed in order to be a much more competitive athlete.

Over a couple of years I started to make these kinds of purchases. (Almost all of the expensive purchases related to triathlon involve the bike so this conversation will really be restricted to that) I got a set of race wheels, an aero helmet, different aerobars eventually a TT bike and so on. Imagine my surprise that despite all of the money sunk, I still was nowhere close to the top third of my age group.

Eventually, I did get there. I have routinely been on the podium of my age group in 70.3 and Ironman events in the last three years and there is no doubt that I do own some fancy stuff. However, I have no problem admitting that it is the athlete who contributes to the successes and the fancy stuff is really just a very minor part of the equation. So here is what I would say to anyone who is in the sport or just starting and wonders like I did, whether they are missing out if they don’t spend their way to be faster.

- Understanding the concept of marginal gains

Coined by David Brailsford the manager of the British National cycling team and later the pro bike team Team Sky, the concept of marginal gains is that if you can eke out the smallest of gains in every aspect of your athlete and their equipment the sum of those gains will be very substantial. For example, remaking the fork of the bike might save 2 watts for a rider. That is not a whole lot. But what if you added to that another 2 watt savings from using a wider tire inflated to a slightly lower pressure. And what if you added to that another 4 W from using a lighter more aerodynamic wheel…and so on it goes. You can see that the original marginal gain from the fork was really not that big of a deal but when summed with all of the other marginal gains you suddenly had a substantial difference.

In triathlon, athletes are similarly looking for marginal gains. Save a little bit here and a little bit there and you will eventually end up saving a whole lot. BUT and this is the crux of the matter, the amount of that savings is going to cost you plenty of money and the results may not be quite as amazing as you think.

For example, there is no question that a carbon disc wheel is a faster wheel than any other rear wheel on a time trial bike. But how much faster is going to depend on a couple of things; how long you are riding it for and how fast you are going. In general, the biggest time savings are going to be for those people who are riding the fastest for the longest amount of time BUT even slower riders get benefits from aerodynamic technology because although they are not moving as quickly, because they are out there for a longer time, they benefit from being more aero for longer.

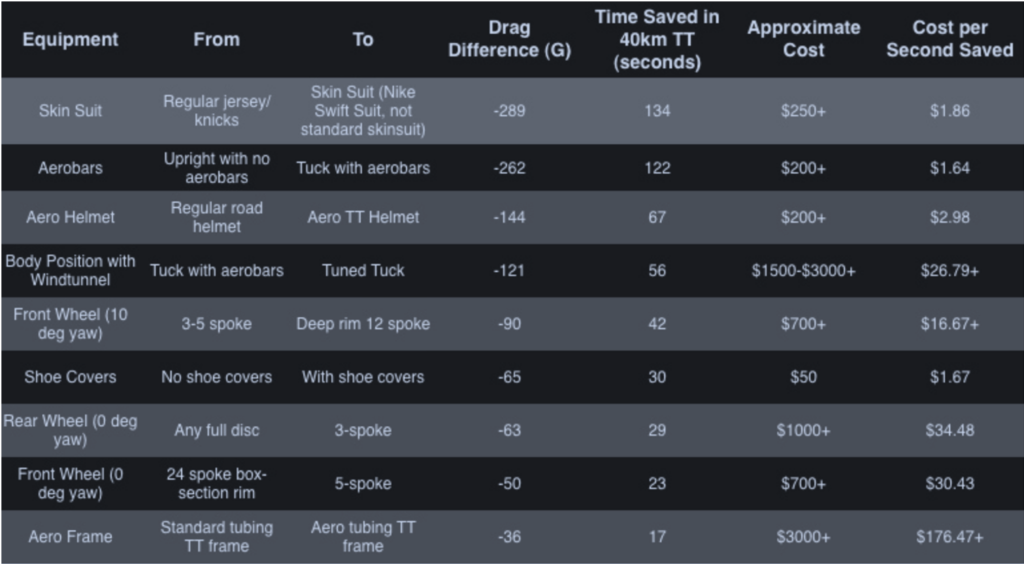

At any rate, a disc wheel is known to save time but you may be surprised to hear just how much time we are talking about. Over a 40km race (standard Olympic distance) the time savings for a disc wheel is 30 seconds over an aero wheel and as much as 2 minutes over a standard wheel. When you figure the cost of a disc being >$1000 that works out to as much as $33/second saved. - Are the gains worth it?

Recognizing that marginal gains are real and that they can be prohibitively expensive leads to an important consideration; are they worth it? That is a difficult question to answer. In practical terms the question is pretty simple-if you are competitive and fighting for a podium spot or a qualifying slot to a World Championship then clearly, every second counts and at that point $33/second likely does not seem like that big of a deal. But for the average athlete, this kind of expenditure does not seem justifiable. However, I certainly understand the emotional intangibles involved here. Afterall there is a world of difference between want and need. - So how do you get faster if you don’t buy the cool toys?

Hopefully you now realize that getting all the latest and greatest tech is not really the key to getting faster and more competitive. Certainly, I learned this lesson the hard way. I spent a lot of money on all kinds of things only to see myself stay comfortably in the middle of the pack for many, many years. I looked super fast, I just wasn’t. Eventually, I did get fast. But it wasn’t through the acquisition of any fancy tech it was simply through a lot of hard work and consistency. Once I dedicated myself to my training and to my goals of becoming a podium finisher and Kona Qualifier, THEN, my fancy and expensive tech began to pay dividends. - Which gains should be prioritized?

There are a lot of ways for you to spend your money and I am not saying that you shouldn’t buy anything, just that you should be thoughtful about how you spend your money. Here is a list of the various things that you can buy for your bike in order to be faster along with the amount of time you can expect to save as well as the costs and the cost per second saved:

Pay special attention to the top three things on the list: properly fitted tri suit, aerobars and an aero helmet. Those three things in sum will cost you no more than a few hundred dollars and will save you a heck of a lot more time than any of the much more expensive things on this list.

The combination of a super bike and a professional fit with aero wheels +/- a disc wheel will get you a lot more savings but this should be saved for more advanced/serious athletes who have no significant budgetary constraints!

One last thing, while not on this list and not something that technically provides marginal gains, a power meter is easily the best thing you can spend your money on to improve your training and racing. If you don’t have a power meter and are serious about your training this is the best tool that you should consider and in fact, I think that training with power will be the subject of my next essay.

What do you think? Was this a productive use of your time? Was this essay helpful to you? As it is the first one that I have done I hope that you will send me feedback to let me know if you liked it or if you have suggestions for improvements.

Thank you as always for entrusting me to be alongside you for your journey to your endurance sport goals!

Jeff Sankoff is a LifeSport Coach, the TriDoc, an emergency physician, triathlete and USAT and Ironman University certified triathlon coach. He works with athletes of all backgrounds and abilities. To learn more about working with Jeff to achieve your triathlon goals, please contact office@lifesportcoaching.com and learn more about Jeff on his coaching page.